Configure AWS Lambda in Java using DynamoDB

AWS Lambda provides an interesting, very highly scalable platform for running functions as a service. You can write a request handling class which will be invoked by a predetermined event such as an external API call, in response to a queue item being created, or on a schedule (amongst others). AWS Lambda will provision some ephemeral compute resources, run your lambda function, and then throw away the underlying nodes afterwards. This ‘serverless’ approach means you pay only for data transfer and the brief time your function is actually executing, which is attractive for cost saving reasons as well as making it easy to compose functions together and scale in an event-driven system (More queue items? Just invoke more lambdas to process them).

Using one of the innovation days that Kainos kindly provides me each month, I’ve been playing about with AWS Lambda because I’ve heard an increase in hype from recent conferences and also because we’re starting to look at this way of developing application services on some of our projects.

The code for the helloWorldFunction lambda is available on Github, which uses an API Gateway to expose access to the lambda using a path parameter as the input request object, pulls in DynamoDB config to set part of the response, and returns a mustache-templated HTML response to the user.

Update

AWS Lambda can now be configured using Environment Variables which makes the majority of this post obsolete. I’m leaving it here for posterity, but if you want to configure your AWS Lambda then using environment variables is the best way to do it.

I’ve now updated the sample Lambda to pull in configuration from an environment variable, which is dead simple.

Runtime configuration

One of the difficulties with using AWS Lambda is that because you don’t provision any virtual machines, and the unit of deployment is basically a zip package containing your jar files (or class files in Python/Javascript land), then there’s no easy way to provide a configuration file alongside your lambda during deployment. Externalising configuration and swapping it out per-environment in order to keep the built code artefact the same is a pretty basic part of continuous delivery, and without environment variables to set on the machine or config files to create in a config folder, this is a bit more difficult.

For configuring Lambdas, until Amazon introduce any more features covering this, your lambda needs to fetch or determine its configuration at startup (and potentially on every subsequent invocation, as storage is ephemeral and so is your code). Assuming you don’t want to bake every environment’s config file into the build artefact (really, don’t) this means one of a couple of options: calling S3 to pull your config from a bucket at function start, or calling DynamoDB to pull your config from a table at function start. Check out the blog post from Concurrency Labs that goes into a little more detail on these choices.

I found the above post very useful in illustrating these options, and I wanted to flesh out the code I’ve created for Java lambdas to pull configuration from DynamoDB using an inferred configuration table name based on the function name or alias.

The ContextWrapper Object

The lambda function in your Java class will be invoked with two parameters: the input parameter defining the request data passed to your lambda (e.g. path, query, or body parameters from a HTTP request) and the context object telling the lambda a little about itself. This context object we take and wrap in an imaginatively named ContextWrapper class which provides a few convenience functions for determining things about the lambda and fetching the corresponding configuration from DynamoDB.

Get Alias ↗

This method is useful for determining the name of alias your under which your lambda is executing. There is no method for this on the context object so it is parsed from the ARN (Amazon Resource Name). If your lambda isn’t aliased then this method returns empty.

Get Environment Suffix ↗

Using a single AWS account for multiple deployment environments means a single shared namespace for DynamoDB, Lambda, API Gateway resources, etc within a given region. If you operate multiple environments like dev, test and prod from the same AWS account then you’ll need to develop a basic naming convention to distinguish between a lambda or an API Gateway resource deployed for test or live usage, so I’m using _dev, _test, _prd for these giving a function name like helloWorldFunction_dev. The environment suffix is parsed out of the lambda function name. If you’re using multiple environments then you don’t need this. If the lambda doesn’t detect it has a _suffix then it returns empty.

Get Deployment Region ↗

If your lambda function is to fetch its config from DynamoDB, it needs to know in which region it’s being invoked. I’ve assumed that we are deploying the lambda in the same region as the DynamoDB exists. Region is parsed from the AWS ARN.

Get Config Table Name ↗

The config table name depends on a naming convention (because obviously it can’t be passed in to the lambda function) and I’ve assumed that we are using a config table named for the lambda name (minus suffix) e.g. helloWorldFunctionConfig for the lambda deployed as helloWorldFunction.

Get Config Item ↗

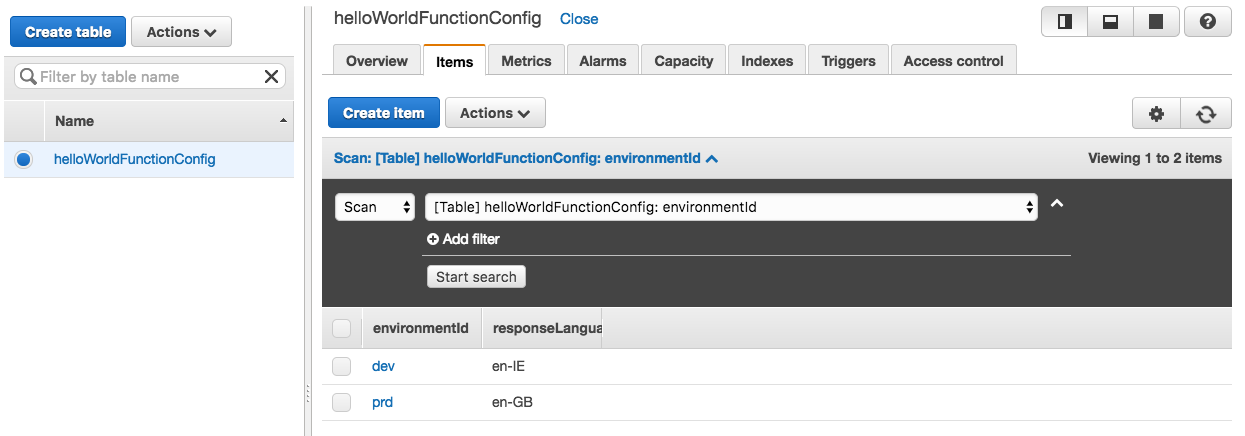

Here’s the useful bit. Having set up a table in DynamoDB with config objects inside, keyed on environmentId determined by the environment suffix above, we can have our lambda open a DynamoDB client to the current region, access the config table, and pull out these items at startup. The DynamoDB and items in this table look like this:

I made a silly mistake with my first attempt at this and used the attribute name ‘language’ which is actually a reserved word in DynamoDB, causing my lookup to fail. D’oh!

Caching Config ↗

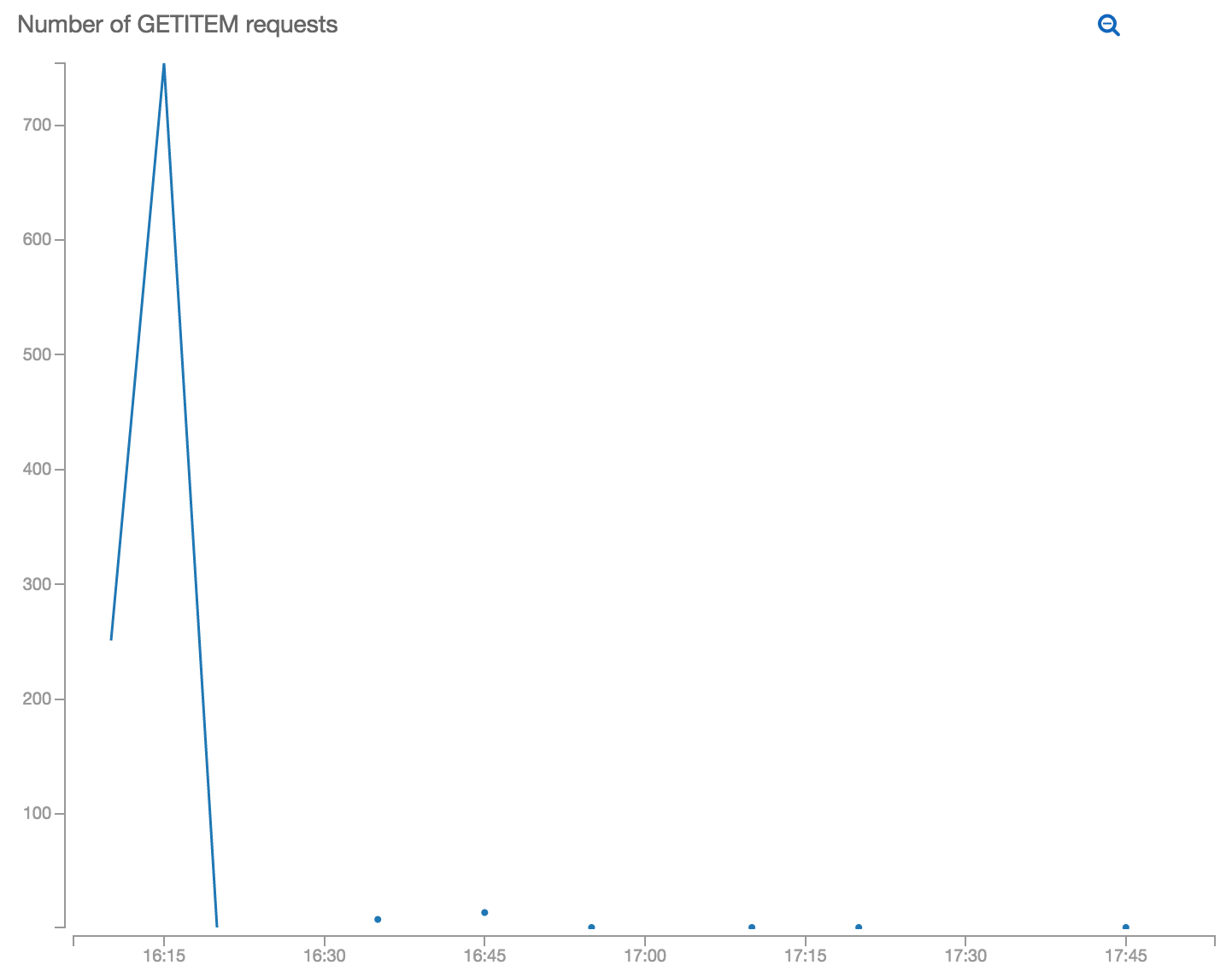

After experimenting with this and deploying it via API Gateway, a clever colleague of mine decided to check if I was watching the logs by sending a large number of requests with amusing path parameters to the public endpoint and racked up a huge bill of $0.03 (Rory moonlights as a pen tester I’m sure). This taught me a lesson about making sure that request limiting is enabled on any unauthenticated public-facing endpoints that I’m testing. However, from looking at the Cloudwatch stats of lambda invocations and DynamoDB usage, it’s obvious that each time the lambda request handler is invoked it fetches the config at startup again - a prime candidate for caching.

Caching was enabled using the incredibly naive and yet totally suitable approach of keeping the config in a class-level variable once initialised. AWS Lambda when executing your function again will be able to reuse the existing container if invocations are close enough together that they haven’t throw out your underlying provisioned resources. On ‘warm’ calls your request handling class will still be sitting there in the JVM with all the variables it had in class level scope when it was last called.

The graphs above show the difference in DynamoDB get requests on a warm lambda before and after caching (deployed at 16:47) - even if someone calls it 800 times in one second you’ll only fetch the configuration item once while the lambda container is being reused. After your lambda’s backing resources go cold and your handler class is reinitialised, it’ll fetch it again (e.g. at 17:20 and 17:45).

Until such a time as there is a way to inject environment variables or other parameters into a lambda, this seems to be the best way to configure your lambdas per-environment without baking secrets into the build artefact.

blog comments powered by Disqus