Making sense of AWS re:Invent

Amazon releases loads of new services

Amazon released quite a lot of new services at AWS re:Invent (check out my previous blog post summarising the main announcements). 61 new services or significant updates to existing services. Clearly they’ve been very busy.

But why these services in particular? What’s driving them to creating these particular features in their platform, and how do they know people will want them? What does it mean for us? My job at Kainos is to build and design computer systems and it means that Amazon (and Azure, and Google Cloud) are constantly changing the playing field when it comes to understanding the landscape of what technology is available to solve your problems and which things you have to build yourself.

It’s not random

Amazon aren’t just releasing services based on what’s interesting to their engineers, or what might be cool. They’re not even just getting their ideas from customer feedback and following market trends. In a lot of cases Amazon are releasing services that just don’t exist out there, for whom there is no comparable competitor - aside from the stuff that people are building themselves.

Part of Amazon’s strategy is and has long been to remove ‘undifferentiated heavy lifting’ - and that doesn’t just mean to go around mopping up all the low level configuration hassle people are having on top of their existing services and turning it into a managed service (e.g. Elastic Kubernetes Service) but they’re pushing further up the value chain towards their customers’ own domains and taking those things people are doing the same across the platform and making those things into new managed services, to build another layer of abstraction on top (e.g. AWS Fargate).

So what does that mean?

What it means is that if your job is to build things on top of computer platforms and low-level abstractions (i.e. most ISVs, development companies, outsourcing companies, consulting companies) then what you consider a low-level abstraction needs to change. At Kainos we focus our efforts on doing difficult digital transformation and development work, and we want to spend our customer’s time and money as best we can to solve the particular unique problems they have and not on low-level things that we have to do just because it’s a required building block.

Take a Machine Learning example

If you want to take advantage of the improved access to large-scale compute and better machine learning frameworks to build a system for your customer that uses machine learning algorithms to, for example, do fraud detection on insurance applications then there’s still a load of work you need to do in order that isn’t actually related to insurance fraud.

Let’s look at a simplified view of the current process of developing this ML based application compared to whether that work is actually stuff you want to do, i.e. related to the problem domain, or stuff you have to do, i.e. necessary heavy lifting in order to get the higher order value out of it.

| Type of work necessary | Work relevant to customer domain |

|---|---|

| 1. Collect and prepare training data | little, when using common models |

| 2. Choose and optimise your ML algorithm | some |

| 3. Set up and manage EC2 nodes for model training | none |

| 4. Tune and trial different model hyperparameters | little |

| 5. Deploy model onto EC2 nodes for production inference use | none |

| 6. Scale and manage EC2 nodes in production | none |

Which really means that to take advantage of machine learning you’ve got to have a strong ops capability, and probably some input from people skilled in data science, and it’s going to take quite a bit of effort to actually bring all that compute power to bear to get your app trained, optimised and deployed.

Well, unless you use AWS Sagemaker.

All of the above work is handled by AWS Sagemaker with comparatively very little effort from you. As I mentioned in my previous post about AWS re:Invent, Sagemaker provides model hosting, Jupyter notebooks, distributed training, hyperparameter optimisation, and a deployment platform. You can use common pre-tuned algorithms or bring your own custom algorithm. You can run your model on Apache MXNet, TensorFlow or bring your own framework. Sagemaker will scale up a fleet of EC2 nodes to distribute your training. Sagemaker will also deploy your model for inference on auto-scaled EC2 nodes and you pay only for what you use when it is invoked.

Once again, what this means is that all this legwork that isn’t relevant to the problem domain, the stuff that all the other people out there also running machine learning systems are likely doing too - the undifferentiated heavy lifting - is taken out of the equation. You don’t have to spend the time, money and effort upskilling to do all of these things when what you actually want to do is about defining your algorithm (or indeed using a common pre-existing algorithm) and applying it to your own domain in the way that you understand is needed for your particular innovation or the problem you’re trying to solve.

Why are Amazon doing this?

Well, primarily because they want to make enough money to build their own moon [Citation Needed]. The best way of doing that is by getting more customers and keeping the existing ones. And the best way of doing that is by creating the ideal form of lock-in, one that Oracle and IBM and the likes abandoned long ago in favour of FUD and punitive licensing because of their corporate inertia: creating a platform that a customer couldn’t possibly imagine moving away from because there are no alternatives with anywhere near the same capability, and because they’ve already got the lowest cost service.

Amazon want to create a platform where people want to keep using more and more because everything you offer them makes their business better at doing what it wants, and reduces their costs and lets them focus on their own market differentiators instead of every company having to implicitly become a technology services company. Amazon are focused intensely on meeting their customer’s needs and finding new things they can do for their customers because they know that’s the way to dominating the market.

Using Wardley Maps to illustrate tech evolution

To extract a general trend and a lesson out of Amazon’s behaviour as a whole, we can take another example and draw it out on a Wardley Map, which will help show us how Amazon’s new announcements have impacted the technology landscape and what it means for people who build computer systems and services on top. This same lesson applies to some extent also to what Azure and Google are doing in the cloud managed service space (and in particular to AI/Machine Learning).

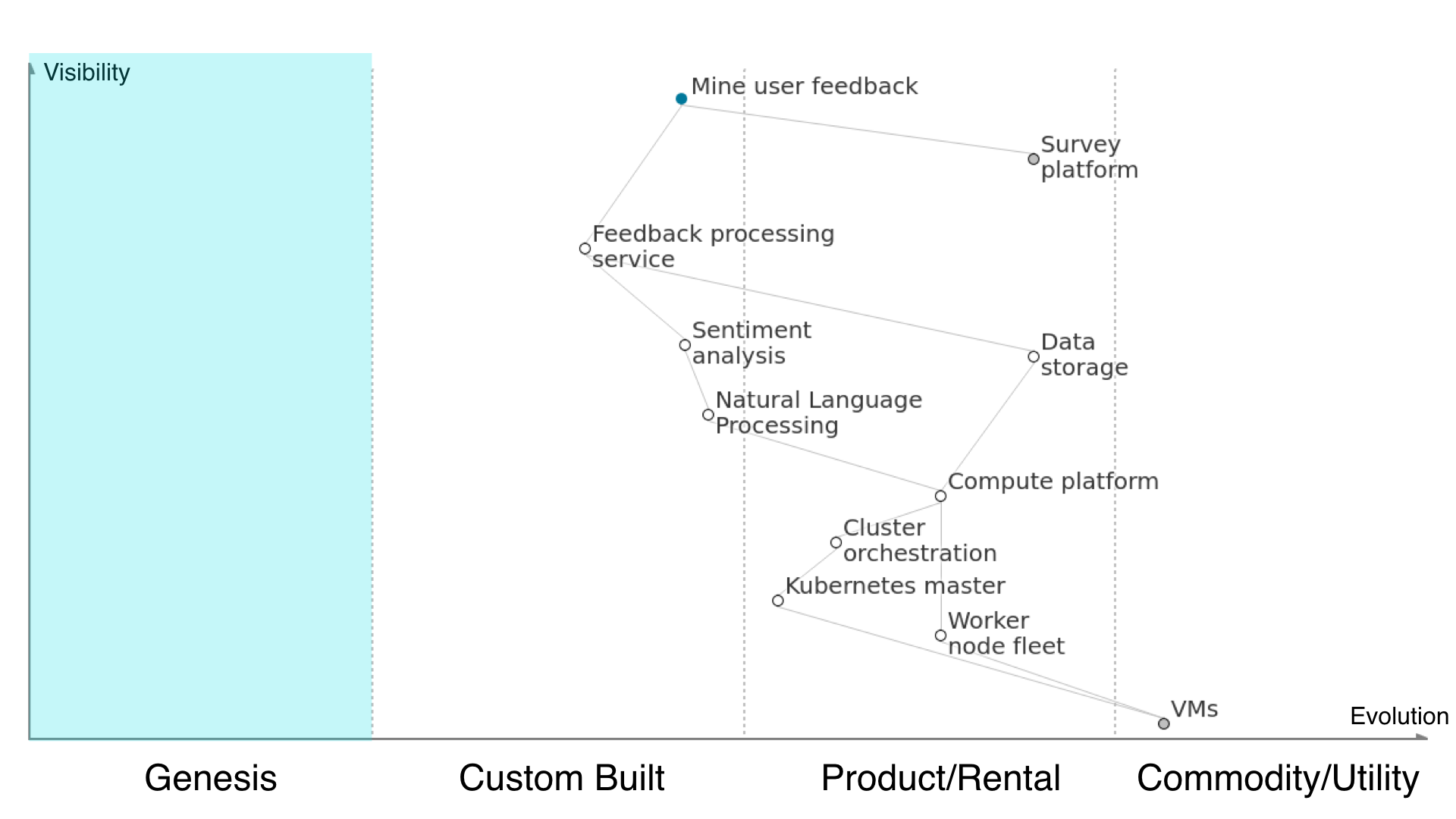

A Wardley Map is a diagram for showing the components underpinning a feature that meet some user need, and their current state of maturity in terms of technology evolution. It shows the position of currently available technologies and how their movement (maturity) or their being replaced can affect other parts of the ‘value chain’ - the dependencies needed to meet that user need. Simon Wardley is writing a book about this technique and has published it all on his Medium blog which I highly recommend, it’s insightful and very readable. I’ll not attempt to cover all the detail or advanced use cases of Wardley Maps in this post, but use a basic one to illustrate the utility.

Start with the User Need

With our Wardley Map, and with any work we do, we start with a user need. In our case, an example from some work I’ve done with a customer recently:

I want to be able to find out from our customer survey feedback what we should actually change in the service

The business person managing the service wants to improve based on user feedback, but there’s so much feedback coming out of the customer surveys that it’s hard to tell the signal apart from the noise. We’ve got thousands of submissions and it’s becoming impractical to just dump it into a spreadsheet and make some user researcher slog through it manually. We want some way to pick out the good bits to share with the team and see what to do more of, but also we want to pick out the bad bits and find which areas we should focus our improvement work on.

Hypothetically then, some analyst and some technical person will sit down and talk a bit more to the business person, then they’ll have a think about what kind of things are best put together to meet this user need, and they make a proposal for a system to meet the need:

Mine feedback exported from survey data using a containerised Python app integrating with an NLP library and with some customised sentiment analysis on top.

Doesn’t sound outrageously unsuitable for this particular user need. We get the data out of the surveys, pump it into an app we’ve written in Python on top of a natural language processing library that we’ve used before, doing a bit of custom definition of what ‘good’ and ‘bad’ feedback looks like in that area to fetch out positive or negative phrases. Obviously we’ll containerise it because that’s all the rage, and the developers insist on it. That probably means we should run those containers in production, which implies lower-level technology choices already.

Understanding the technology evolution scale in Wardley Maps

The tech evolution axis shows where along the path from completely new idea to undifferentiated commodity components are. The main sections: genesis, custom build, product/rental and commodity/utility describe technologies that have been adopted to different extents and that the offerings will have different characteristics depending on their maturity.

Genesis is where people are inventing entirely new products, techniques or ways of doing things. Perhaps a problem is being solved for the first time. In Kainos, a lot of the work we do in R&D comes under this section.

Custom Build is where we’re doing stuff that is specific to the customer’s own needs. Where we’re creating something just for their business, or doing something in their domain first time, or automating and improving something that hasn’t been computerised before.

Product/Rental is where we’re plugging reasonably well defined things together, where we’re taking systems and products that already exist and figuring out how to combine them or use them to meet the customer’s need, or handing them over to services.

Commodity/Utility is where we’re relying on utilities or underlying platforms that you can just assume exist without really having to think about them. Typically this is things like power, internet connection and so on. Competition amongst vendors here is usually on price, with little differentiation.

Mapping the technical solution

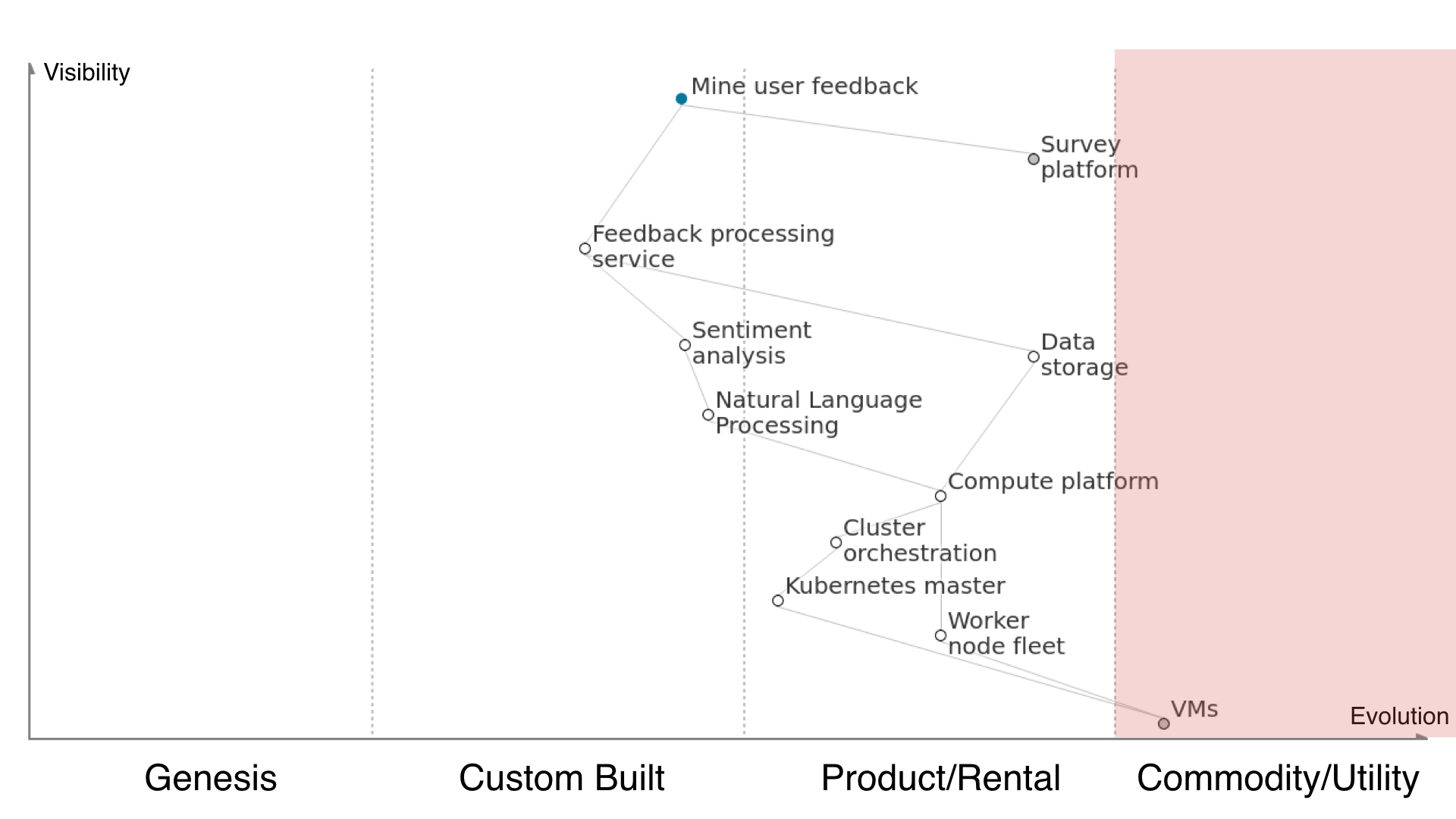

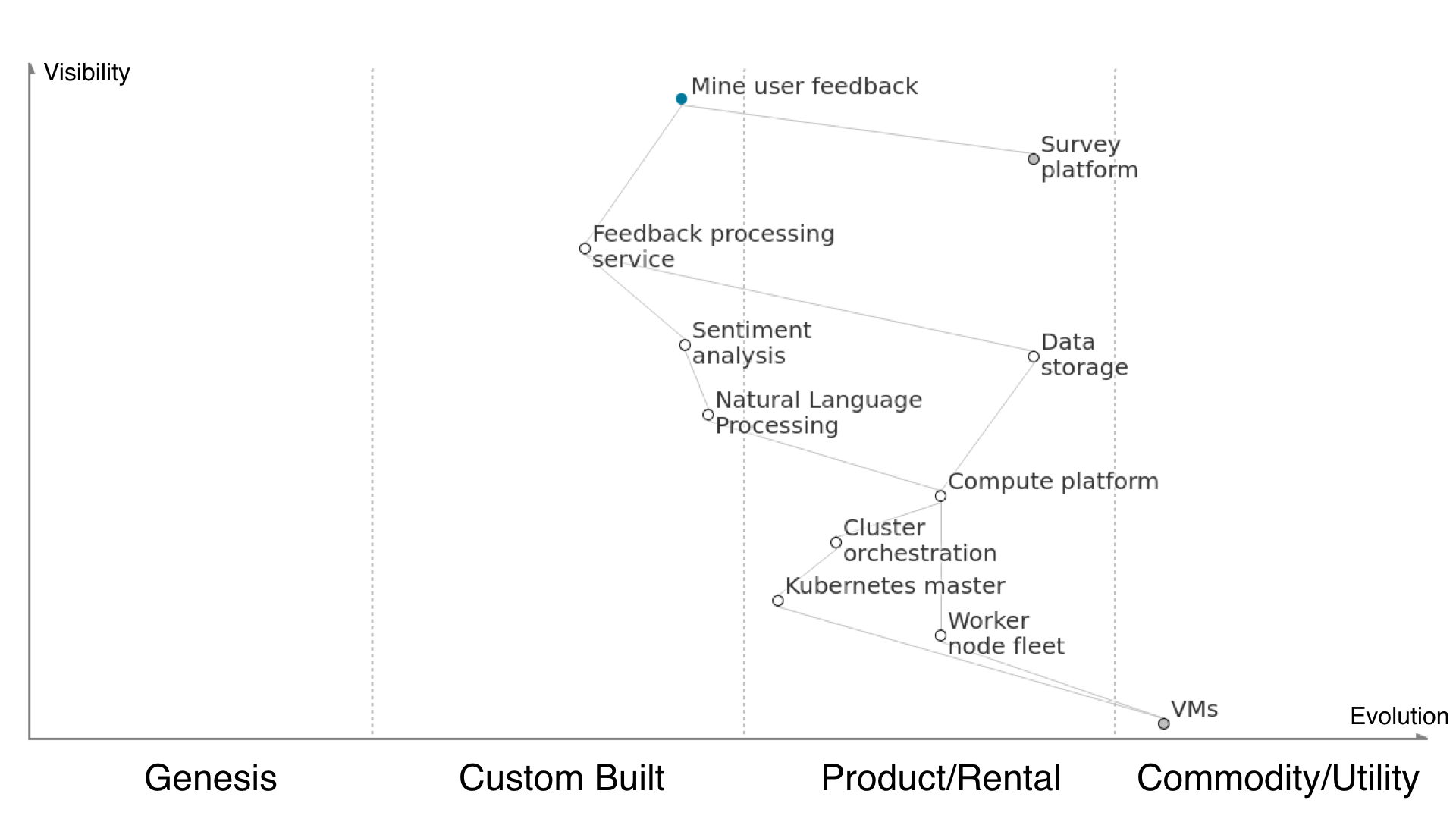

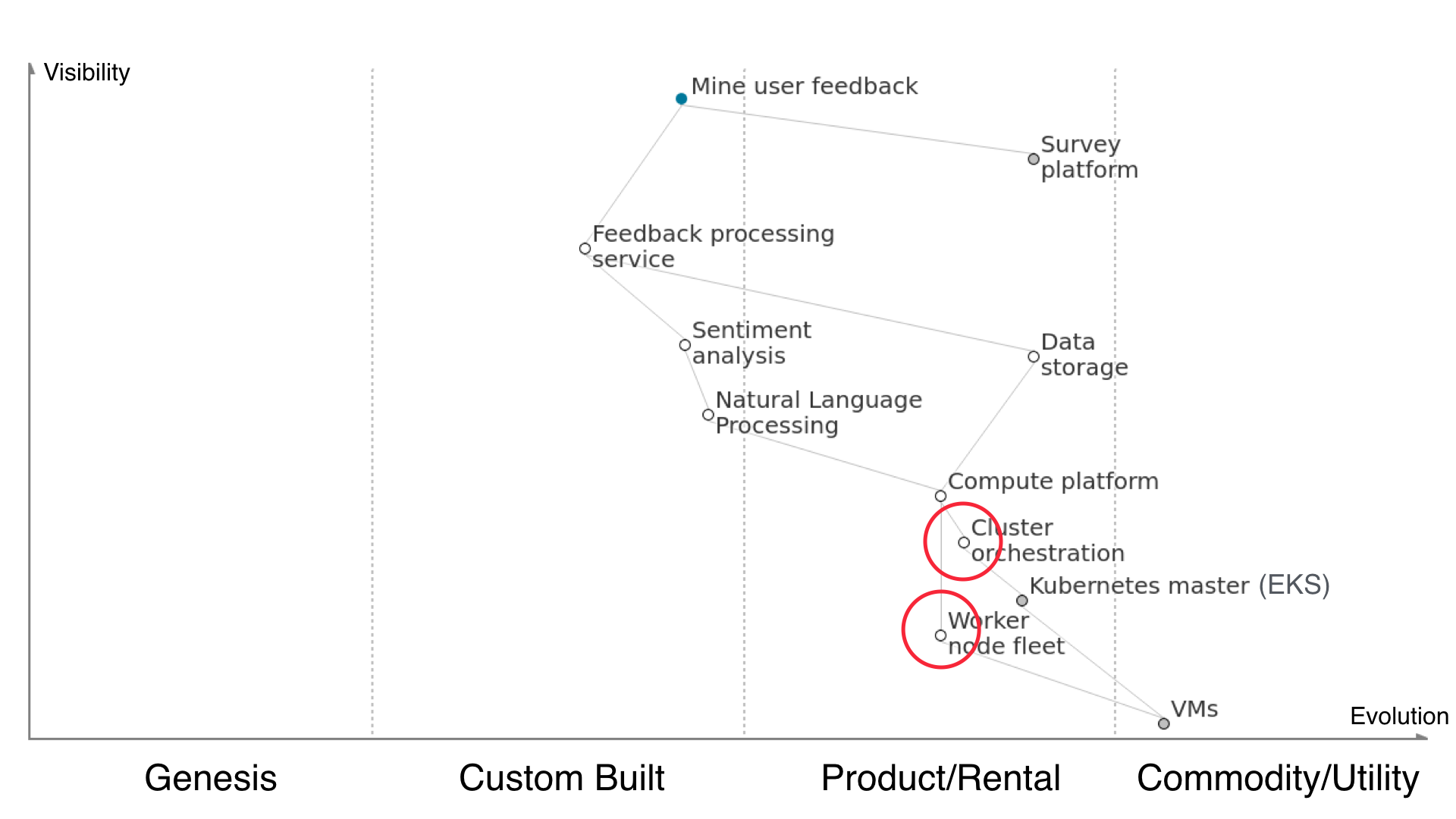

This is the Wardley Map for the service proposed to process user feedback from survey results. Let’s take a look at the components it displays and how they relate to each other, where they sit on the technology evolution axis, and how the components are broken into a chain of dependencies from the user need down to invisible to the user but necessary.

Firstly, we start at the top with the user need. In order to mine user feedback we must use the existing survey platform (outsourced, grey circle). We must create a feedback processing service to effectively get meaning from the survey data without having to use manual effort, which is in the ‘custom built’ area of the technology evolution scale, as it is being put together by us in this way for this customer for the first time but it’s likely not the first time anyone has done it.

The feedback processing service depends on having the data from the survey platform extracted and kept in a data store somewhere, but that’s wee buns so we’ll hand that off to Amazon S3 or something similar. Storing data is pretty well understood and straightforward, so it lives in the ‘product/rental’ part of the scale due to being fairly undifferentiated. The processing service also depends on our Python sentiment analysis application, which we’ve picked due to it being somewhat commonly used for this type of work, though our having to detail what we consider good and bad is still fairly hand-cranked.

The sentiment analysis application depends on the natural language processing library, which itself is open sourced but requires some tweaking to fit our use case and be plugged into our application. Running an NLP library in our application depends on a compute platform underneath to actually execute our code, and this is in ‘product/rental’ territory because we know there are many services out there that’ll help us host a system built from containers. If we’re running containers and we care about high availability, rolling upgrades, fault tolerance and taking good advantage of underlying compute resources then we’ll need a cluster orchestration tool. In our case, we’ve picked Kubernetes because everyone is talking about it and it’ll look good on our CVs it’s rapidly becoming the de facto standard for running containers in production.

Running Kubernetes for cluster orchestration means we’ll need to run a couple of Kubernetes master nodes to actually operate the cluster for us, and we’ll need to provide it with a fleet of worker nodes for it to allocate out the pods onto in order to get the service up and running. Configuring the Kubernetes master is a bit complex and difficult and that’s not just something you can press a button and have done for you when your underlying building blocks is managed VMs [no spoilers please]. Managing a worker node fleet sits further right on the tech evolution scale than this because it’s quite undifferentiated work to spin up EC2 instances and assign them to autoscaling groups and subnets and the likes.

Underneath our worker nodes, we’ve got virtual machines. As far as we’re concerned these days, running a handful of Linux virtual machines is a totally commodity service. Insert coin, press button, receive VM. Every cloud provider does it and at that level they only really compete on price. It’s totally undifferentiated work and that’s exactly why in this solution we’re definitely not going to manage the virtualisation ourselves. Friends don’t let friends build data centres. I’ve gone no further in the value chain (e.g. down to network, power, etc) because it doesn’t really add any value on this particular map, as everything underneath is just utility services. If you’re a datacentre provider deciding who to use for your redundant power supplies, you’ll probably want to map out that part but for us it’s fine to leave it as far as we need to be relevant.

The effect of Amazon on evolution and the proposed solution

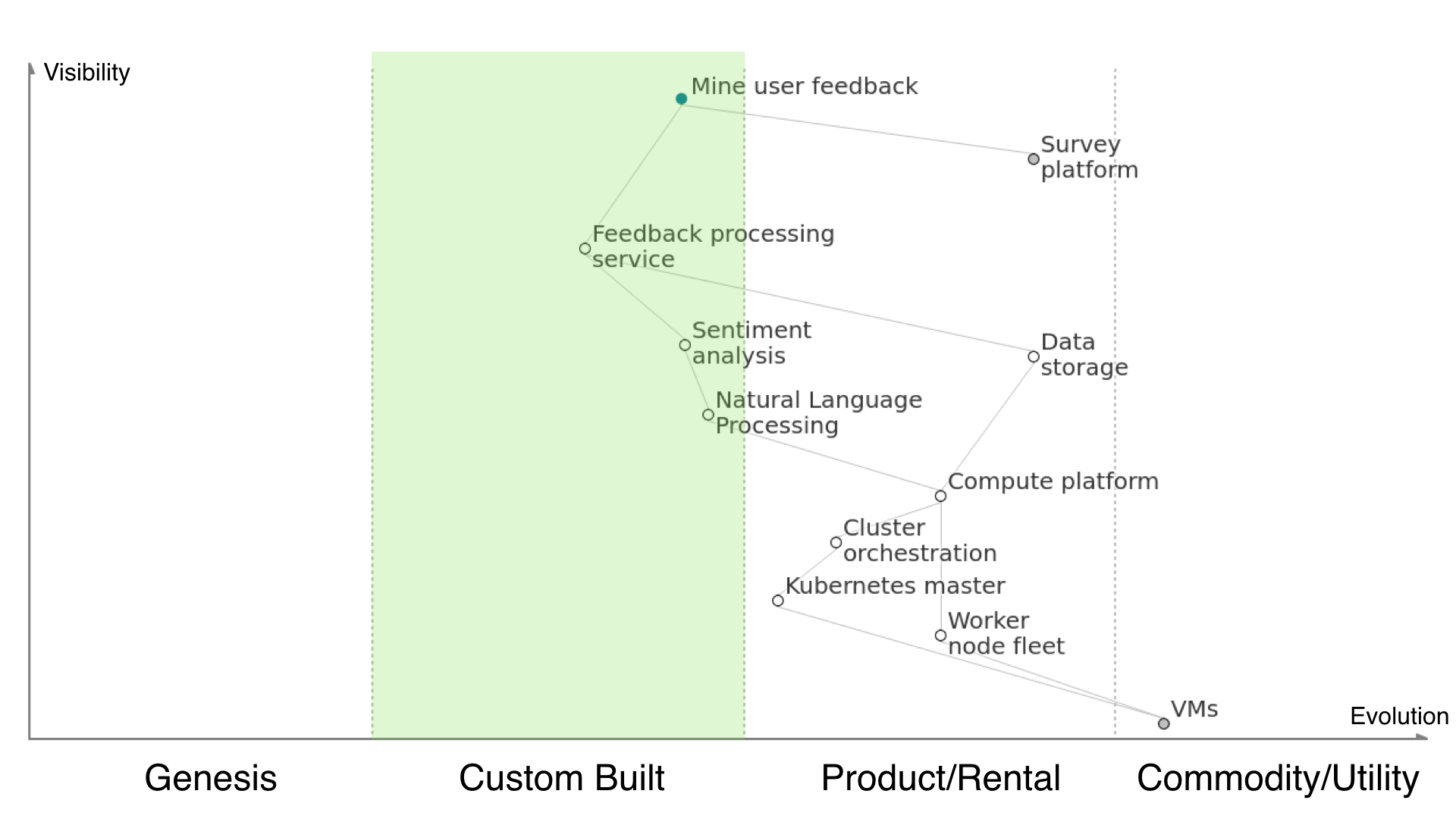

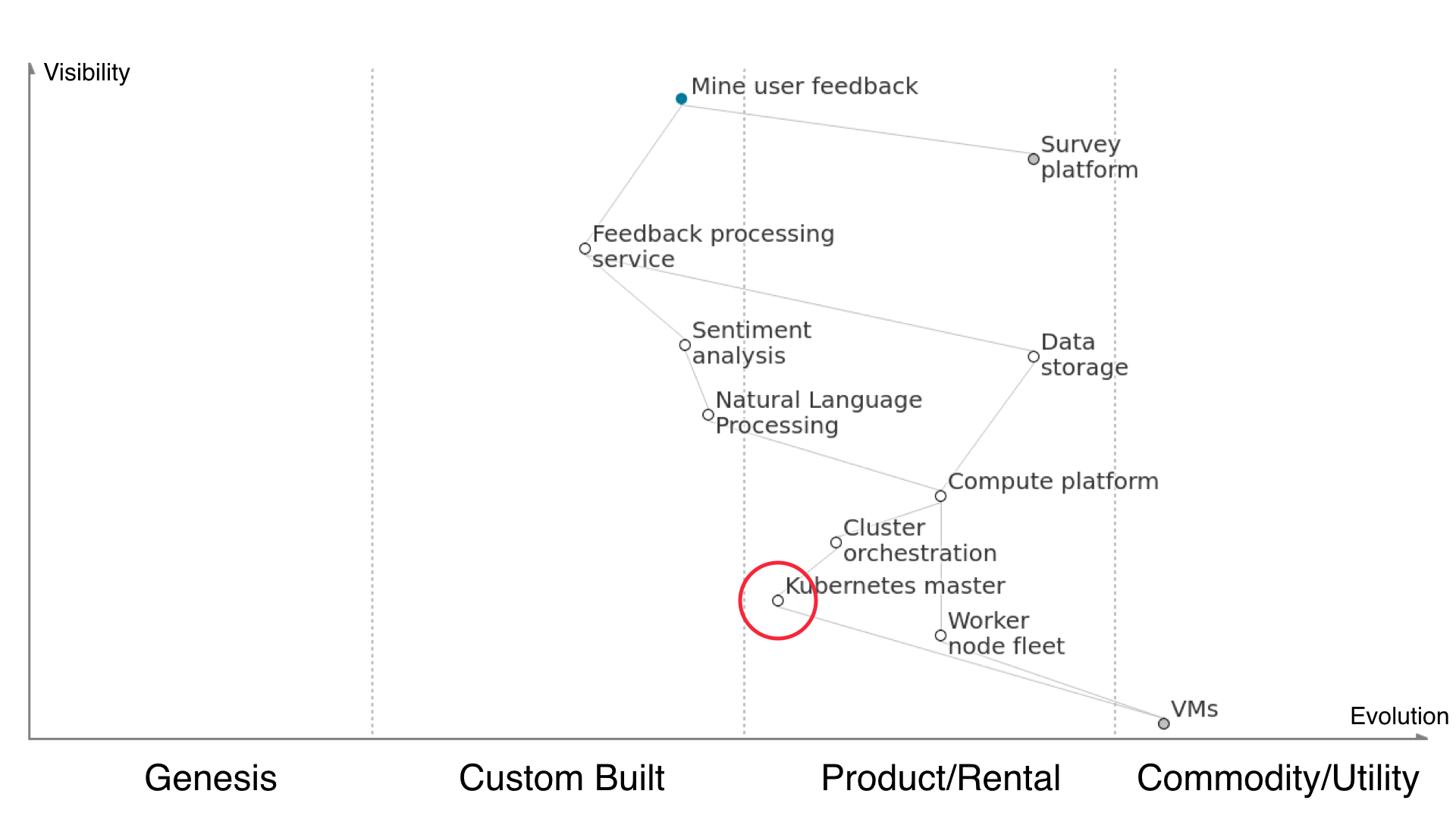

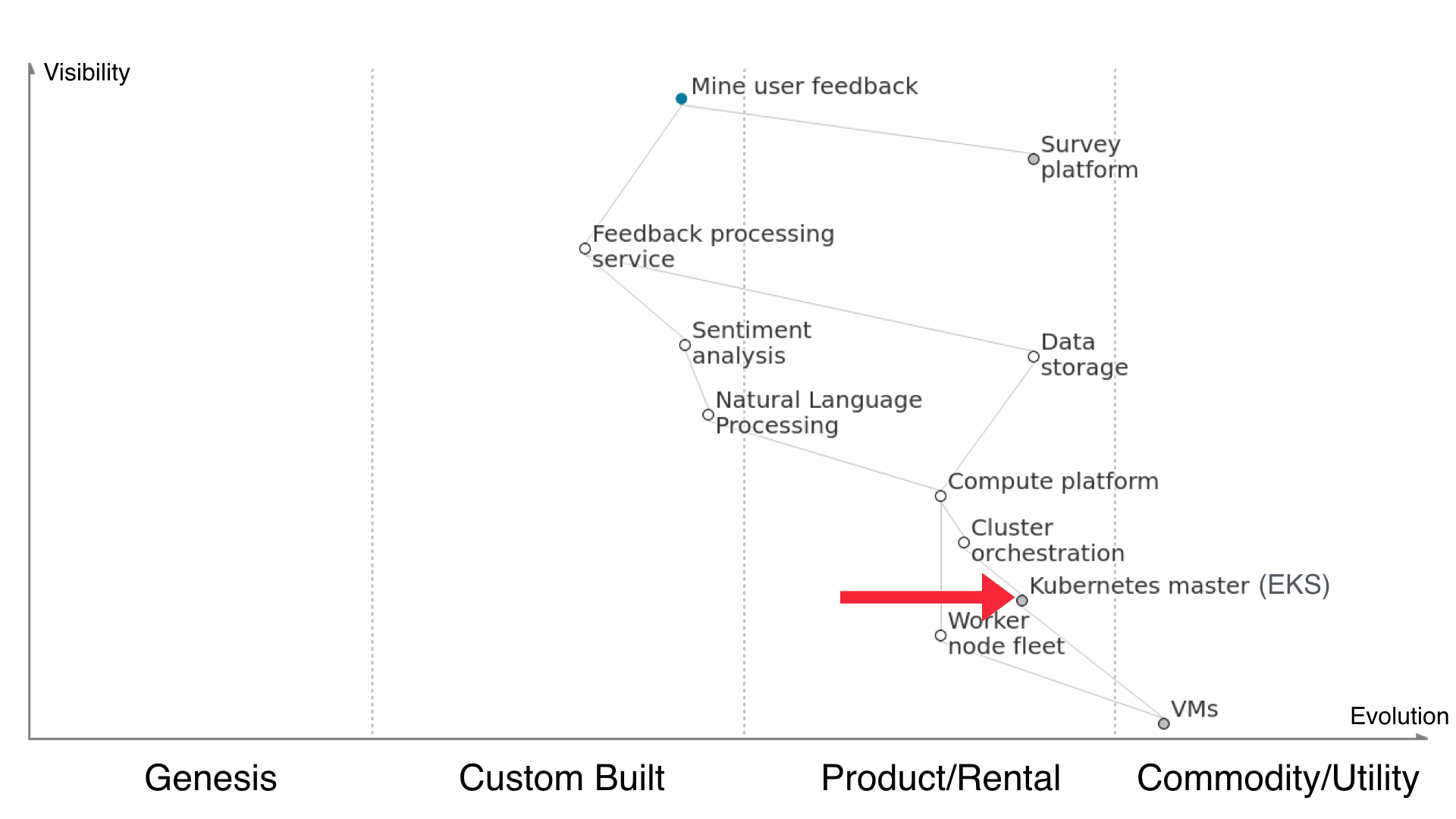

So how do Amazon’s new announcements affect our proposed solution? For some of the tech components we’re proposing laid out on the map above, maybe we don’t have to configure or hand-craft or manage ourselves. Let’s see how the new product announcements affect the position of those components on the map.

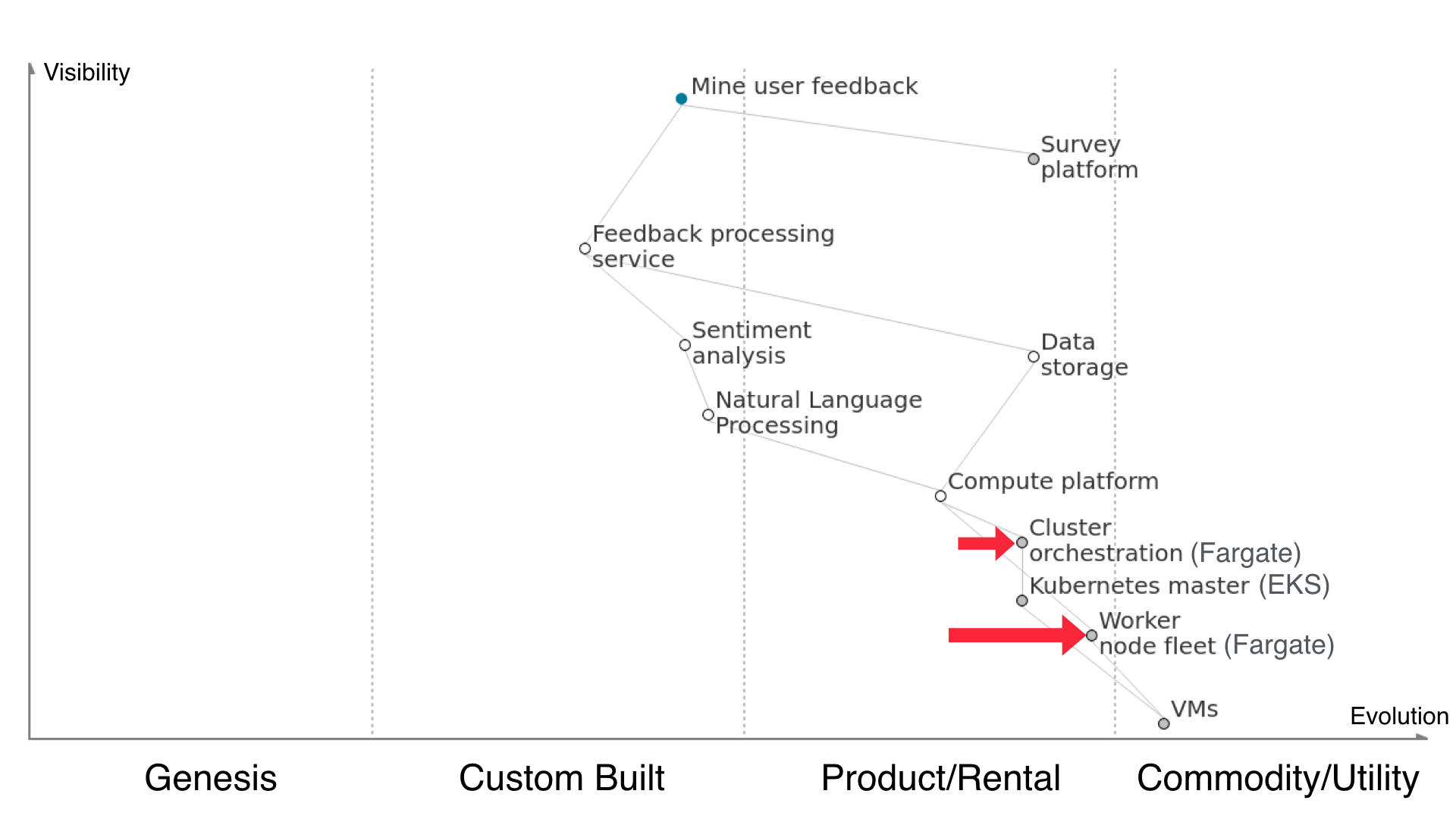

Here’s Kubernetes, our chosen cluster orchestration master. It’s a bit of a hassle to manage and configure ourselves, and plenty of other people have been saying the same thing, so AWS released EKS to run your Kubernetes master nodes for you in a high-availability setup.

What that means is that Kubernetes shifts over quite a bit to the right on our map. Managing a Kubernetes master setup is now something Amazon EKS will do for you, taking away the undifferentiated work.

Next up is the rest of the ‘how to run containers in production’ heavy lifting. Managing a fleet of worker nodes, provisioning them, patching them, attaching them to Kubernetes - that’s a goner now with Amazon Fargate. Fargate supports managing ECS tasks at the moment and will support EKS in the next number of months.

That takes the entire cluster orchestration dependency off our plates. We have to neither manage a k8s master nor the workers. We just give Fargate our container definitions and throw money at the problem until clustering happens. Kubernetes becomes simply an interesting detail of how the cluster runs.

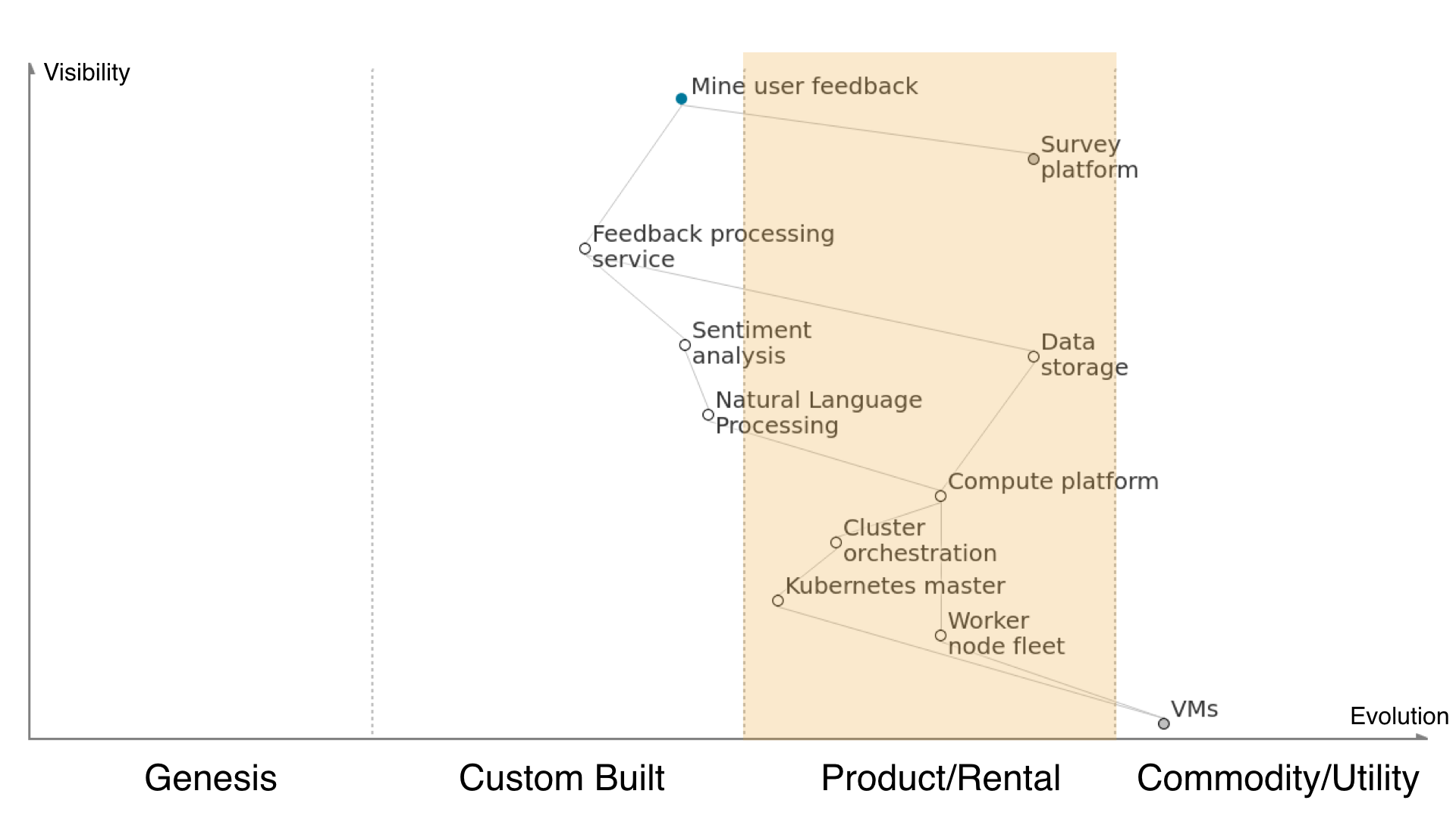

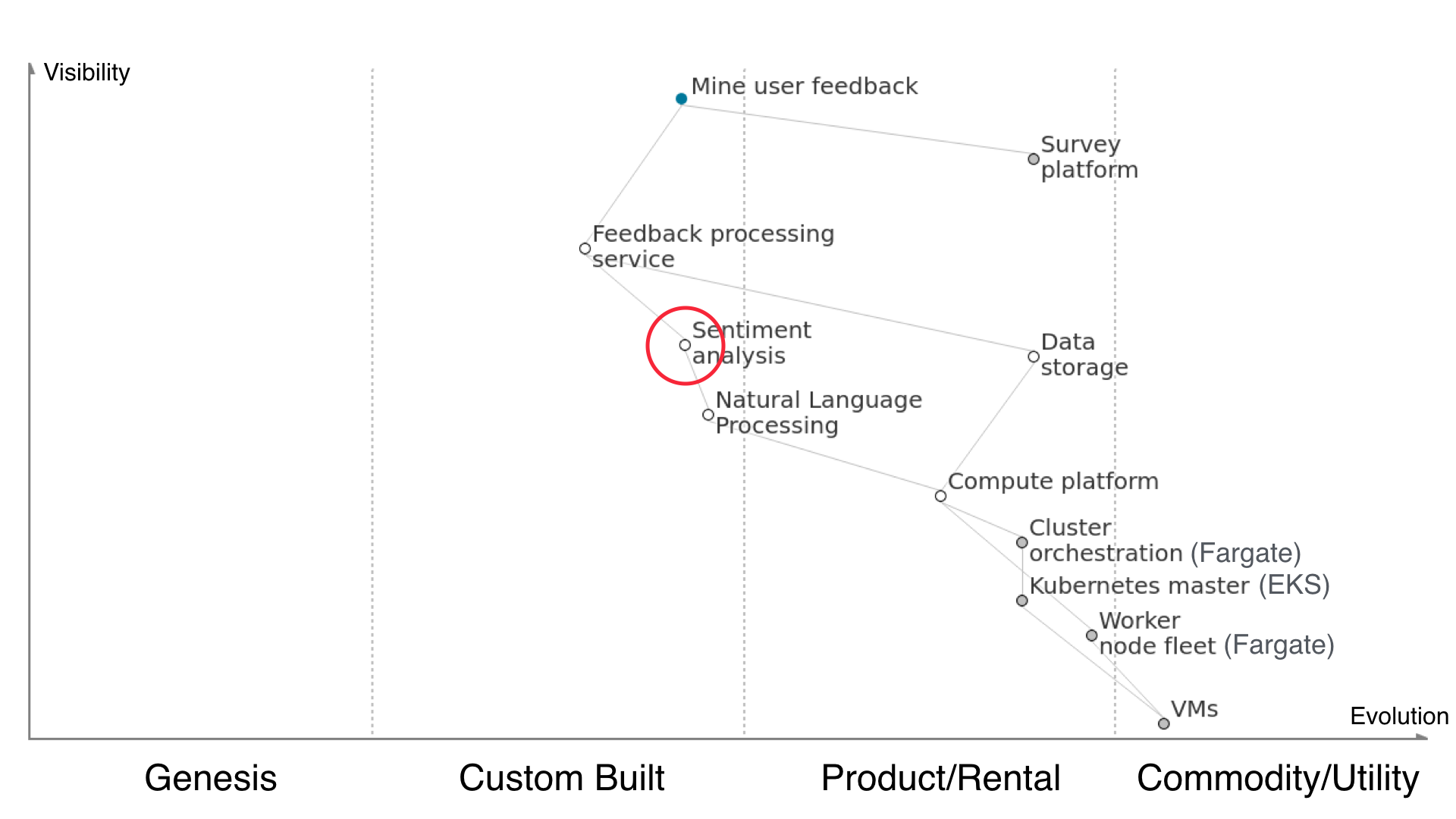

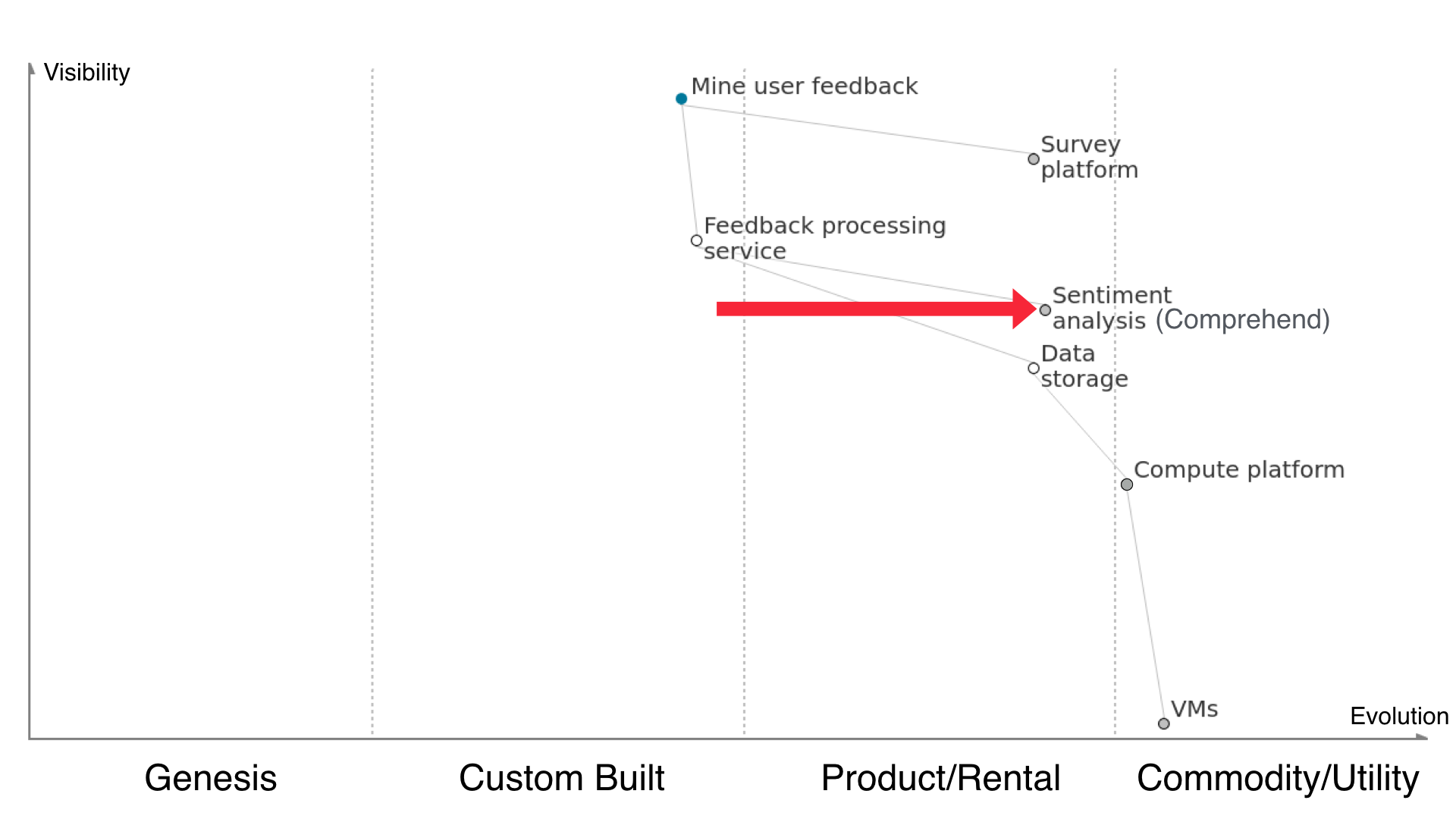

But what happens when Amazon releases Comprehend, a service that does natural language processing and sentiment analysis? For the sake of time and effort any rational mind would want to utilise this, unless their specific use case falls right outside the realms of what this text processing, topic extraction and sentiment analysis as a service offers. So we use Comprehend in our solution instead.

You don’t need that set of applications any more at all. You don’t need your custom sentiment analysis code built on top of the NLP library, you don’t need a compute platform because it’s all abstracted away from you, and you definitely don’t need containers or VMs or anything like that. The whole compute platform is an outsourced utility as far as we’re concerned. We have no interaction with it, and only know it exists by virtue of the fact that our sentiment analysis service is running somewhere. We just use the outputs of the service.

Wardley Maps can help

Wardley Maps can help you make technology selection decisions when you’re creating or proposing new systems, and they can help you understand the landscape of the industry and available options when you’re deciding where you should focus your efforts if you’re an ISV or development house.

Using a Wardley Map can help identify which are the areas that Amazon might be likely to target for new services next: we know they’re going to move up the value chain and try and identify areas that many customers are doing the same work as each other but which isn’t relevant to their own problem domains.

If you’d mapped out the major cloud platform provider services and the type of work that many people are doing on top of it at the start of last year, you’d probably have been able to predict that Amazon would release EKS. And I don’t just mean because during the year Azure released AKS and they were now the odd one out - but because it’s an obviously popular service and a common type of work people are doing on EC2. 63% of Kubernetes clusters running in the cloud are run on AWS, after all.

Avoid doing undifferentiated heavy lifting

We can use Wardley Maps to illustrate the tech selections you are making on a project and identify where we are doing customer-valuable work and where we’re doing heavy lifting. When we’re mapping out a component and saying “we’ll have to build that ourselves” there’s an opportunity for each of the dependencies we say that for, to go and check our assumptions with what’s actually available out there and see if we’re making the best use of it.

If you’re implementing low-level configuration type work, or anything else now offered by an AWS service, you’re essentially now competing with Amazon. Redoing that work that the platform can do for you isn’t just a waste of your time and money, but in a consulting/development business it means that your competitors can pitch for the same work as you and claim to do it faster and cheaper while you’re repeating work they can take for granted.

Take advantage of the platform first

If you’re configuring VMs and installing PostgreSQL version whatever and pulling your hair out over setting up the clustering configuration, you could just be using Postgres flavoured RDS and spending the rest of your time in the problem domain. Many organisations are well beyond the “should we use RDS?” discussion and this same discussion will repeat itself further up the layers of abstraction as PaaS and managed container orchestration become much more widely adopter, and we move towards greater adoption of function as a service.

In the majority of cases, following these new service announcements, we will be able to stop worrying about how to configure Kubernetes masters in cluster deployments with high availability and use EKS. Indeed we can likely in some cases stop worrying about clusters at all and just hand containers (and $$$) to Fargate and let it deal with the lower levels. We can stop worrying in our ML work about how to do Hyperparameter Optimisation of our fraud detection model and use Amazon Sagemaker to host, train, optimise and deploy it. We can go back to figuring out how the user need is actually met by things that run in parallel with high availability, or how the user need is met by training the fraud detection algorithm with certain characteristics.

Probably don’t build your business one step up from the platform

The type of work which is “log in to EC2 instance and install $thing and then configure clustering” is most at danger of being turned into a managed service if many customers are doing it. That’s exactly how we got EKS and Amazon MQ, after all.

Take EKS for example - there were a few vendors in the exhibition hall at AWS whose business model of “we’ll install and run Kubernetes for you” was pretty much destroyed by the announcement of EKS. Investing in productising or making a service offering out of things one step above what Amazon are offering is a risky proposition unless you’ve got a compelling differentiator or the work you do isn’t easily replicated across different types of customer.

Building stuff hasn’t gone away

This isn’t to say there’s no point in an R&D effort in Machine Learning now that Amazon Sagemaker exists - quite the contrary. AWS doesn’t do everything, it does the base cases, and knowing where their service doesn’t meet our specific needs is important. We should use this in the standard cases to take the less valuable work out of our hands. I feel generally that you need to understand as far down as one layer underneath the layer you want to take advantage of, for when the abstraction leaks and so you’ve got sufficient knowledge to know when to use the abstraction and when to stop shoehorning your problem into the shape that someone else’s solution fits.

But generally, move up the value chain

Understanding of the platforms and how they work is important, and occasionally you’ll want to go lower level to get some specific niche capability - but that’s how you should treat it. Unless you work for a company whose actual core business is in providing these kinds of platforms, then the bulk of your work should be done at higher levels. Look at PaaS over IaaS, evaluate Lambda seriously, prefer managed services by default. I’d go so far as to say that in most cases, Infrastructure as a Service isn’t for you, it’s for Amazon and Azure and Google’s own service teams to build stuff on top of. What you want is to then build on their offerings instead of duplicating them. If you don’t do it, your competitors will!

tl;dr Cosmic Brain meme

blog comments powered by Disqus