Automated Testing and the Evils of Ice Cream

The Software Testing Pyramid

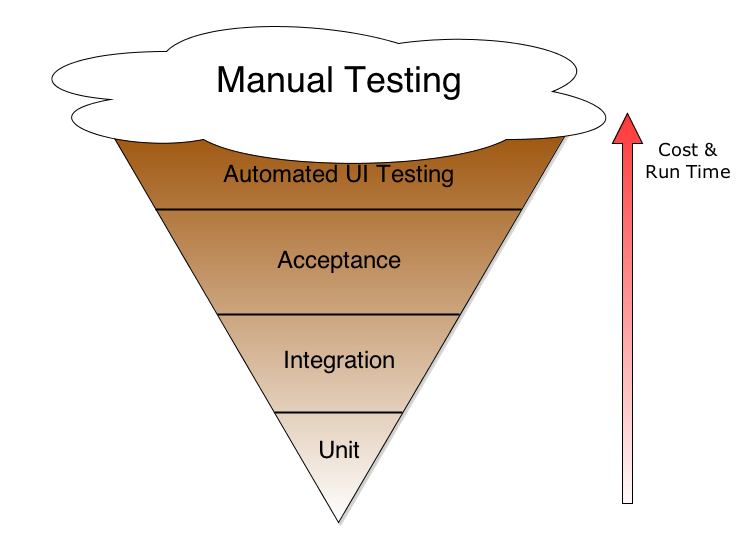

This pyramid diagram illustrates the ideal breakdown of software testing on a development project. This diagram was inspired by Mike Cohn’s blog post on automated testing and shows the ideal distribution of tests across different levels of abstration.

Unit Tests

Unit tests should be the most ubiquitous tests in your codebase, testing the many permutations of the execution paths where execution time is in milliseconds and the time to prepare, write and assemble the code fixtures needed for testing is minimal. Whether you go the whole hog and use TDD or if you write your tests after the fact, if you can accompany your code with reasonable coverage of happy & sad paths and boundary cases at the unit level, starting this way and taking the time to continue on will lead you towards a good result. There are many technologies that can enable this, from JUnit through to RSpec for almost every platform.

Integration Tests

When a component is complete, write a few tests that describe the interactions it has with other components. Some of these should involve mocking to test simply that the correct interfaces are being called on your services, and some (but lesser still) should test that the services can be executed and real data can pass between them. These two aspects of component testing and API testing I interpret as being in the ‘integration testing’ section of the pyramid. These tests execute a little slower than the unit tests as they need to either fake or really invoke other components but these should still be reasonably fast. Integration testing usually takes a little more orchestration than unit testing but you should be able write a basic script to mimic your continuous integration build process to call maven, sbt etc to build your dependencies and execute tests.

Acceptance Tests

Acceptance tests should be used to describe the user paths through the operation of the features being developed, at sufficient level to be reasonably implementation detail independent and also to be used as acceptance criteria for the features under development. Some like to write acceptance criteria in Gherkin style to then wire up to test fixtures and use these plain-English descriptions as both documentation and tests. I like this practice but would only use it where actually valuable; where business users are going to be involved in defining and negotiating the executable test definitions. If you can’t have that kind of interaction and only devs/testers will be reading and writing these tests, perhaps the indirection is not worth it. Use your judgement.

UI Testing

User Interface level testing should be kept to smaller sets and to truly valuable test cases to ensure that a good RoI on the time spent creating and fixing them, given their fragility and longer execution times. UI tests should test that page flows through user interaction heavy features are sane but avoid testing all permutations of good and bad test data through the UI given the needless repetition that this creates in testing the slower code that fires events in the UI controller, sends data to and from the services behind the scenes and updates the interface again. It is valuable to test that this process works but testing many permutations of some kind of calculable result should be done at a lower level. Selenium WebDriver and PhantomJS can handle scripting UI level tests for you.

Manual Testing

Manual testing should have a place to fulfil the needs of testing that can’t be automated. In reality this is very little. Testers should provide more valuable and heuristic verification: sanity checking for whether someone has set the ‘buy’ button to transparent in colour; ensuring pages look right in ways that is difficult for automated UI testing to verify; general exploratory testing. Though these manual tests are all good to have, but not so much that you need to rely on them to regularly prevent problems. Ideally these forms of testing would catch the very rare bug - more obvious or serious bugs should be detected much faster and earlier in the pipeline before they get to this stage. Think of a night watchman looking for broken windows as he walks past the house, rather than going inside checking the contents of each room to ensure nothing is missing.

Automation

Every time you write one of these kinds of tests, or describe the steps involved in a methodical, repeatable and prescritive way so that a manual tester can execute it, you should be automating it. Automated testing should not just mean load testing or browser-based UI testing. Save the testers of the world from going quietly insane from running boring and predictable input-output checking tests and let them get stuck in to the more non-determininstic program-breaking (where they usually excel) and in helping developers identify edge cases and ensuring acceptance criteria are understood.

When starting out on a greenfield project, this is easier to achieve through the discipline of ensuring responsible levels of tests are created as development on features progress. If you have a ‘definition of done’, describe the expectation of testing (e.g. “unit tests must test correct, fail and boundary cases”, “basic acceptance tests must exist for each one of the acceptance criteria” kind of thing. I don’t like hard and fast rules on percentage of code coverage ). When you do this, you are creating a safety blanket of testing as you go along. Every new piece of work can be demonstrated both to function correctly, and to not break any of the existing tests in the system. Think of it as getting regression testing for free!

Test automation itself is simply a case of basic scripting nowadays, once the tests are written and the code itself is testable. Whether this is mvn test, rake test sbt test or vstest.console.exe depending on your platform, this should be easy enough to add to a script which you should run every time you save changes to your code locally. Get into the habit of running your newly automated tests every time you make a change and you’ll catch things that would otherwise be found later.

When trying to stabilise an existing or legacy project with tests, achieving this balance is harder. Seek to avoid the ice-cream cone of testing.

The Ice-Cream Cone of Testing

Don’t let its tasty looks fool you; this is one cone you don’t want to be eating. Dan North described the ice-cream cone of testing during his Accelerated Agile class this year at QCon and I also recall briefly seeing a similar diagram on the watirmelon blog some months back.

In the testing ice-cream cone, the pyramid is inverted and the abundance of cheap, extensive, fast unit tests is replaced with an over-reliance on expensive, slow manual testing and fragile, slow automated UI testing. This seems more common when a project has not started out with an intention to create clean and testable code suitable for unit testing but instead has bolted more and more testing on to the top as defects and reduced quality exposes a lack of acceptable test coverage. The pain this causes is that testing is slower and more fragile and software development cycle time suffers.

I’ve also seen this pattern on systems where a company has invested heavily in after-the-fact testing on a legacy system that has little to no testing through either throwing a large number of testers at the system, or spending big money on lots of UI based testing (sometimes even lots of the slow and brittle click-record type testing). This is harder to thin out but effort must be taken to push testing further down the layers where it is easier to cover many paths and faster to execute, both to reduce the cost of developing new features but also to improve build and test times.

Fight Back

When working with an existing system in this state, it is rare to be given the time and effort needed to re-invert the cone. Instead, gradually push testing back down the cone by ensuring that every new feature created for this existing system comes with automated unit tests and integration tests instead of just a suite of extensive UI or manual tests. Ensure that every time a bug is fixed, the test case that identified that bug is refactored into unit tests and demonstrate that this is sufficient to test if the bug is present.

If the codebase is too gnarly and interdependent to make the unit tests you want right now, try mocking or just make do with integration tests. At least you are pushing in the right direction, but as new features are developed and added ensure that you have written them in well encapsulated form using appropriate interfaces and segregation to allow you to test the new code with unit tests and to mock out its dependencies. Every time you visit the codebase you should be making it a little better.

Now you can start arguing about the value of some of those UI test cases that you’ve got covered at lower levels. Take back the build-test-deploy times!

blog comments powered by Disqus